In the beginning of his book “Being There Together – Social interaction in Virtual Environments” Ralph Schroeder (2011) provides a definition of Multi-User Virtual Environments (MUVEs):

The VEs discussed here relate to virtual reality (VR) technologies. In a previous book, I defined virtual reality technology as ” a computer-generated display that allows or compels the user (or users) to have a feeling of being present in an environment other than the one that they are actually in and to interact with that environment” (Schroeder 1996: 25; see also Ellis 1995) – in short, “being there”. (Schroeder, 2011, p. 4 – original emphasis)

And from this follows that MUVEs can be defined:

(…) as those [virtual environments] in which users experience other participants as being present in the same environment and interacting with them – or as “being there together.” (Schroeder, 2011, p. 4 – my emphasis)

In line with Schroeder’s definition, the term MUVEs is sometimes used exclusively to characterize virtual environments designed on a 3D spatial metaphor (i.e. Ketelhut, Dede, Clarke & Nelson, 2006), because this is seen as a precondition for experiencing presence when there is an emphasis on the “there” component in the understanding of presence. However, in the field of distance education, the concept of presence has been debated for decades, and has included the sense of self and sense of others that do/do not occur also in 2D virtual environments. Most notably the work of a Canadian research project referred to as “Community of Inquiry” (COI) that ran from 1997-2001, managed to bring focus to the concepts of cognitive, social, and teaching presence as being essential to especially distance educational experiences. The COI project started with a focus on presence in text-based computer-mediated communication (i.e. Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000; Rourke, Anderson, Garrison & Archer, 2001), but has since moved on to also study these particular types of presence in 3D virtual environments such as Second Life (i.e. McKerlich & Anderson, 2007; McKerlich, Riis, Anderson & Eastman, 2011). The difference, between Schroeder’s perception of the presence concept and that of COI research, highlights the fact that there is no (cross-disciplinary) consensus on the definition. In fact, many definitions and sub-categories of presence can be identified, and this is evidently something I’ll discuss thoroughly in my PhD.

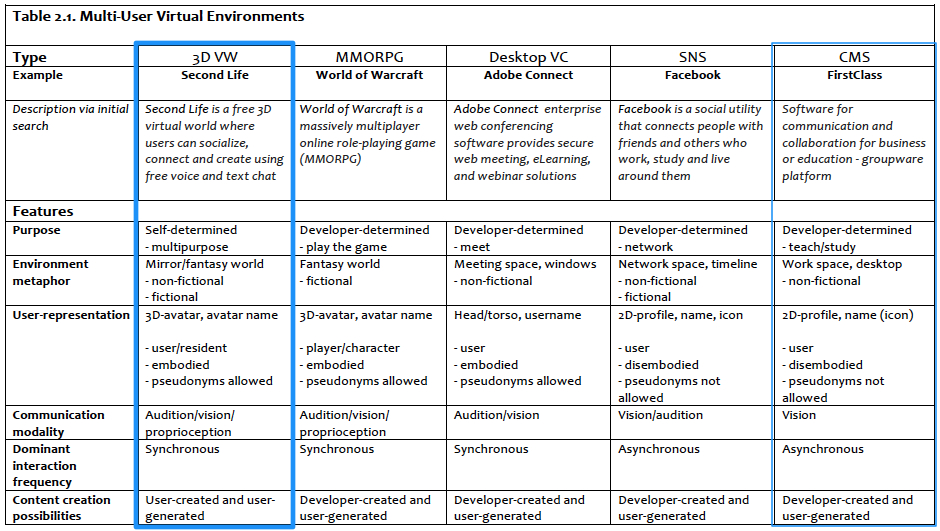

It is important to notice that the primary focus of my study is on Second Life. Nonetheless, other types of MUVEs cannot be ignored simply because both the research literature and the participants in my study often refer to these other types in an attempt to make sense of Second Life. In the table below, I’ve provided an overview of the different types of MUVEs that are relevant to have in mind as part of the overall context of my study.

Clearly, learning happens in all these MUVEs, but from a formal educational perspective, there are some very interesting differences between these different types of MUVEs. Among critics of VWs, I’ve often heard the argument that “VWs are just virtual learning environments based on a spatial metaphor”, and while it is true that VWs, such as Second Life, are based on a 3D spatial metaphor and that this is an important difference, it is not the only one. To me, the communication modalities, the interaction frequency, and not least the content creation possibilities offered in these types of virtual environments, are just as important.

In my study, the teaching and learning processes have been situated in a blended environment consisting primarily of a combination of Second Life and the more conventional 2D virtual environment called FirstClass. At the Master’s Program of ICT and Learning (MIL) that I have used as case for my study, FirstClass provides the ICT infrastructure in this distance ed program, this is were the majority of the administrative and teaching activities take place – the students tend to use complementing technologies for their learning processes. During my research period (2007-2011), the use of FirstClass and Second Life has changed: in the first research cycle, the majority of both teaching and learning activities took place in FirstClass, whereas in the final, fourth research cycle, Second Life provided the setting for the majority of the activities. Regardless of this, I still believe both environments contribute with some unique affordances that are important to ensure high quality teaching and learning – and ideally, none of them should be used as stand-alone environments.

/Mariis

References

Garrison, D., Anderson T. & Archer, W (2000): Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2: 87–105

Ketelhut, D. J., Dede, C., Clarke, J., & Nelson, B. (2006): A multi-user virtual environment for building higher order inquiry skills in science.Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

McKerlich, R. & Anderson, T. (2007): Community of inquiry and learning in immersive environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 11(4).

Rourke, L, Anderson, T., Garrison, D.R., Archer, W. (2001): Assessing social presence in asynchronous text based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 50-71.