Yesterday, in a talk at The Federal Consortium for Virtual Worlds (FCVW) conference, Jim Blascovich spoke about reality, virtuality, and our perceptions hereof. Blascovich made some interesting and provocative claims about reality, starting with the question: “What is reality?” and answering it by saying: “No one knows!” Blascovich then presented a photo of the Earth and a photo from SL, and asked are they both real? Yes! Are they both virtual? Yes!

Um, so at first glance this may seem confusing, but as far as I understood it Blascovich’ point was that our perceptions (of anything) are idiosyncratic hallucinations, and we see/perceive things that are not there and things that cannot be there – the human brain adapts and “right things” (cf. the work of George Stratton on perceptual adaptation). Together with Cade McCall, Blascovich explains this in a paper on “Attitudes in Virtual Reality“:

“In contrast to the continuing struggle and debate among interested scholars over the hard consciousness problem, many scholars from many fields concerned with the question, “What is reality?” agree that what people think of as reality is an hallucination; that is, a cognitive construction. Together with religious gurus and mystics, philosophers (Huxley, 1954) and experimental psychologists (e.g., Shepard, 1984), maintain that perceptions are invariably idiosyncratic hallucinations, albeit often assumed and treated as collective. (Blascovich & McCall, 2009, p. 3 – my emphasis)”

I don’t know … I think this is difficult to comprehend, and I couldn’t help but think about Plato and his cave-analogy. Based on a question from the twitter-audience, I did get the impression that Blascovich recognizes the empirical world (our Earth) as real though; because he went on to make the distinction between “grounded reality” and “virtual reality”. However, the tricky part is that what we consider “real” or “virtual” depends on our individual perspectives, and this is referred to as the principle of psychological relativism:

“Analogous to Einstein’s theory of special relativity regarding time and space, psychological relativity theory states that what is mentally processed (i.e., perceived or thought of) as real and what is mentally processed (and thought of) as not real (i.e., virtual) depends on one’s point of view. People contrast a particular “grounded reality”— what they believe to be the natural or physical world—with other realities they perceive—what at times they believe to be imaginary or “virtual” worlds. However, what is thought to be grounded reality and what is thought to be virtual reality is often muddled or even reversed. (Blascovich & McCall, 2009, p. 4 – my emphasis)”

While I really appreciate Blascovich’ emphasis on “context” as being crucial to our perceptions, I think the problem with relativity is that it makes it very hard to reach consensus on anything, or to achieve “collective hallucinations” so to speak – and for many people the uncertainty of relativism is unsettling. Whenever I bring students into SL, they clearly struggle with such ontological questions, and I think the uncertainty about what is/isn’t real can become a barrier to adaptation of the medium.

Fortunately, it isn’t all completely relative. The research done by Blascovich and colleagues (not least Jeremy Bailenson – cf. Infinite Reality) shows how i.e. movement, anthropometric, and photographic variables influence our perceptions. And by studying such results, we – as VW designers/users – can accommodate different perceptions and it gives us a more informed starting point for some very interesting discussions on the ontology of VWs.

Admittedly, I’m still processing some of Blascovich’ points in terms of consequences for VWs design, and I’m not sure if it makes sense or if I can make sense of it … according to Blascovich “reality is a state of mind”, and mine sure is messy!

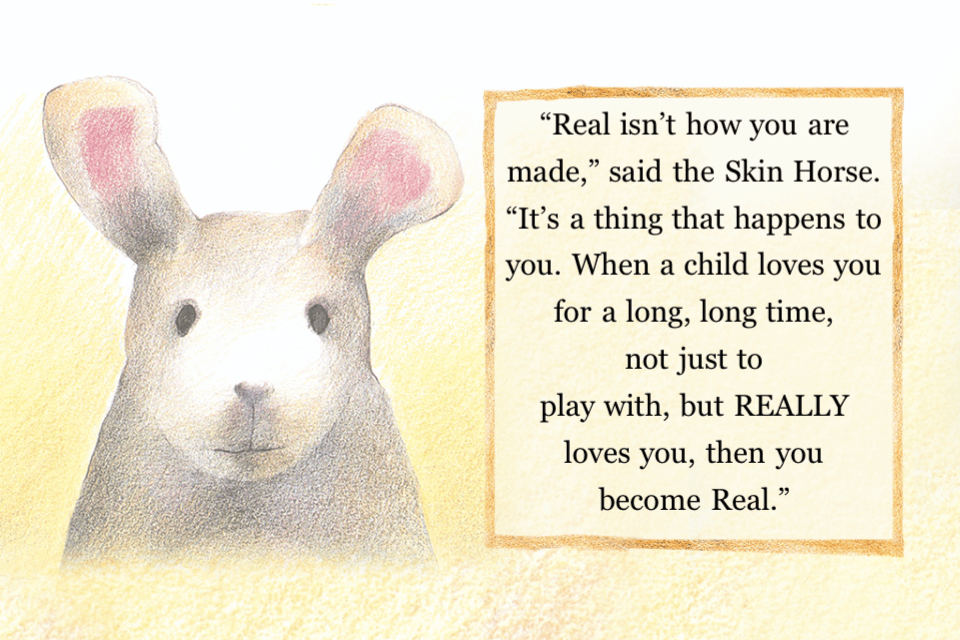

Without diminishing the work of Blascovich et al. I still think that one of the best explanations of “real” stems from a dialogue between a rabbit and a wise old skin horse:

/Mariis

Setting up the three presentations in the sandbox.

Setting up the three presentations in the sandbox.

Ready to embark a gondola ride into the rainforest.

Ready to embark a gondola ride into the rainforest.